There is beauty in the ordinary. Waking up, making coffee, washing my hair, going to the post office. All ordinary things made extra-ordinary because I am here to do them. I woke early and watched the moon sink and the sun rise. The east screamed tangerine and the sun pierced the thin veil of sky with a restless yearning – as if it needed to be seen by human eyes so it had proof of life. ‘I am here!’ it bellowed through the clouds.

Not surprisingly, I was much the same when I woke up following my transplant surgery. I was still intubated (on life support), and my first physical response was to try and pull out the tube that was down my throat. I remember Dad finding me a notebook and giving me a pen so that I could write, but all I could manage was scrawl and for a few seconds, I thought I was brain-damaged. But was I even alive? I could see Mum, Dad, my sister Nikki, my boyfriend Lachie and one of my best friends, Laura. Someone then found Dad an alphabet board, so I could point to the letters. The first letters I pointed at were -

‘A M I A L I V E’

Everyone laughed and nodded their heads, saying ‘yes, you’re here – you’ve made it.’ Then I pointed out the letters ‘I L O V E Y O U’ and I couldn’t tell if everyone was laughing or crying or both. All I wanted to know was if I was alive, so when I knew for certain, I started thrashing around on the bed because the tube down my throat was choking me. At least that was how it felt.

For the next three days, whenever the sedation wore off, I would thump around like a frightened yearling and try to pull the tube out. That was until a nurse rushed at me and pushed more sedation through the I.V in my neck. What surprised the doctors, was that I needed about five times more sedation than the average patient of my age and size. They worked out it was a combination of stubborn and a high tolerance for not only sedatives, but barbiturates, general anaesthetics and opiates.

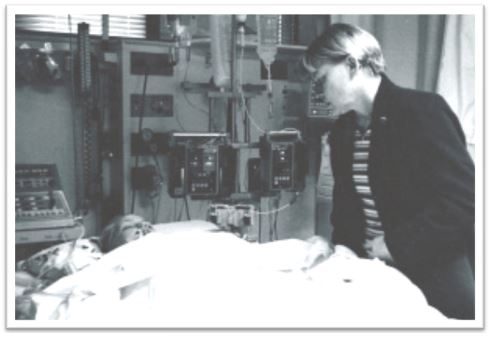

Here’s Mum watching over me. It saddens me to see the distress etched along her cheekbones and forehead. I often wonder how much this experience both eroded and strengthened her.

My friend Sharon, who introduced me to Alicia (they were studying the same course at the Queensland College of Art), and my Mum are smiling here because they can see that my fingers are pink after having been cyanotic (blue) from the lack of oxygen in my blood for so long. The fact that Sharon would cry and faint at the sight of a needle and/or blood (I remember her screaming when we had to have our TB immunisation at school), she did incredibly well with all of the needles, tubes and machines. Sharon has since had three babies and can now deal with blood. I’m very proud of her evolution.

When I initially went on the transplant list, I was told that I would more than likely have a long wait because my lungs were so small, which meant that I might need the lungs of a child. This never sat well with me. It was like a stone in my belly. Knowing that I was essentially waiting for someone to die so that I may live was an already heavy burden, let alone knowing I may end up with the lungs of a child inside me who had not lived a long enough life, often made me feel physically ill.

This is what an end stage Cystic Fibrosis lung looks like. I always liken it to a dead bat.

Transplant is a mental and moral minefield. A girl I had grown up with could never reconcile the fact that she had another person’s lungs inside of her, and she died a couple of years after her transplant full of that terror. During a transplant assessment to determine if you’re medically viable for transplant, among the barrage of tests is a psychiatric evaluation in order to ascertain if you’re stable enough to endure the possible mental rigours that go hand in hand with having such life-altering surgery. The transplant team has to know if you’re going to be compliant. Are you going to take your medication religiously? Are you going to look after yourself when you leave hospital? Do you have adequate familial and emotional support to cope post-surgery? If the patient has emphysema, will they start smoking again? Unfortunately the answer to the last question can be ‘yes’. I’ve known patients who have taken up smoking post-transplant, and I can only imagine how this makes the doctors and other medical professionals feel. Personally, I want to give them a high-five. In the face. With a SHOVEL. I want to repossess their lungs and give them to someone who deserves and respects them.

For me, having a transplant is a shared responsibility between my donor and I. It’s a shared duty of care. They’re not my lungs – they’re ours. I’ll say ‘my lungs’, but what I really mean is ‘mine and hers’.

I was extubated (taken off life support and breathing on my own) after three days and I didn’t stop for talking. For days. Mum, Dad, Laura, Lachie and Nikki were never far away. And neither was Sharon, my Blood-Sharps Princess Warrior :) Lachie would often leave me writhing in pain because he made me laugh so much …

My first walk with Mum in tow. Always with me.

My favourite ICU nurse, Allan. He did a superb job of extubating me, so I love him extra hard.

But like any journey worth writing about, it wasn’t all beer and skittles/sunshine and rainbows. In the second week, I began to wheeze and it became steadily worse over a weekend. I was home on day pass and I bounded up the stairs where I did a Rocky victory jig (except that no one was watching). I let everyone know that I’d made it to the top of the stairs without dying, and I noticed I was wheezing.

‘I must have got an asthmatics lungs,’ I said, and everyone clapped at my efforts and laughed at what I had said about my wheezy lungs.

Scott Bell, my lung transplant consultant, was sick that weekend, so another doctor – a heart transplant consultant (hearts –> chalk/lungs –> cheese) assumed that it was asthma and so prescribed me nebulised ventolin. The problem was that it wasn’t asthma and by Monday morning, I was critically ill with the worst rejection Scott had seen up until that point. I had essentially been misdiagnosed. Scott was not happy. You don’t get Scott unhappy.

I had bronchoscopy after bronchoscopy, was moved back into acute ICU for an afternoon for observation and my morphine dose was increased. Rejection was the worst pain I had been in since the epidural had been removed a week earlier. When the epidural was pulled, someone may as well have poured fuel over my chest and set it alight. I’d never suffered – really suffered – with pain so fierce and searing before, and I’ve only experienced it once since and that was after my cancer surgery in 2007. In my ‘Transplant Diary’, where Mum and Nikki wrote everything down every day, Mum writes on the 31st August, ‘Carly is in extreme pain, like someone is sitting on her chest. She is having morphine.’

The other drug they increased was my prednisone (cortico-steroids). Massive doses of methyl-prednisolone pulsed through my body for three solid days, as well as other drugs you’d think would be better at stripping paint off the walls. My doctors were calling transplant units all over the world to try and save my life, and though we knew the rejection I had was serious, it wasn’t until six months later that Scott told me how close I came to dying. Even when I see Scott now around the hospital, he still shakes his head and says, ‘I’ll never forget that rejection. It really was an extraordinary time.’

There’s that word again. Extraordinary.

But I’m more than happy with ordinary. Ordinary means simple, and simple is beautiful in its truth and brevity. After I spent some time with my folks and two of my closest friends, I stopped at a shop which has everything that I love – coloured wooden blocks, cotton socks, porcelain birds and winsome stationery – and I bought a teapot and the matching cups that I’ve been looking at for a while. It brews a lovely cuppa, and every time I pour from the pot and drink from the cups, I’ll think back to this ordinary day in all of its staggering and miraculous beauty and all of its blessings.

Without my family and friends, I am nothing. I am a body with a stagnant soul ♥

I’m *very* spoilt …

Here’s to our shared good health ♥

(From bruisesyoucan touch.com)