Today, a tribute to the talented and indomitable Carly Jay. Please read her extraordinary story.

If you would like to consider being an organ donor see this link: http://www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/services/medicare/australian-organ-donor-register

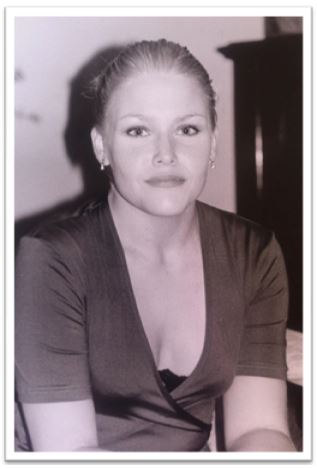

I’m finding it hard to concentrate on my study today. It’s that time of year. It’s Transplanniversary* time. The 22nd will mark sixteen years since I was (at least this is how it felt) thrown back into life after being ripped from the tenuous march to death. This is a photo me on my 21st birthday on New Years Eve (my actual birthday), 1997. Between Christmas and here, I knew I had to put myself on the transplant waiting list. I’d been remarkably unwell at Christmas and the days after, but by some strike of grace, I was pulsed with energy for my twenty-first birthday. Looking at this photograph now, I look so serene and calm. Just like any normal kid. I look at this picture and think, ‘Pretty. Pre-transplant boobs. No scar. BT. Before Transplant.’

But when I peel away the layers of this photo, I was anything but a normal kid. I had the weight of my life on my shoulders (and someone’s eventual death who would save my life) and it burned my bones to ash. I didn’t want to be on the transplant list for my birthday, so I put my beeper away for the night and partied for nearly three days with friends, some of whom had come as a surprise from overseas, because some people were in on the fact that this might be the last party I’d have. My mum knew. My Dad didn’t. Mum knew because she had been there every single day, at every corner of my de-evolution. While C.F snapped at my heels, we tried to keep the multiple infections at bay with brutal anti-biotic regimes and towards the end, months of hospitalisation. Mum had also seen so many of my and her friends die while waiting on the transplant list, or not even get on the list at all. They simply just died.

My Dad is an eternal optimist and for quite some time, thought I could possibly regain some of my lost lung function. He was both optimistic and in denial, so the day that I literally couldn’t get out of my boyfriends car to look at my new room, he knew things weren’t looking good for me. I knew that he knew, and I remember feeling an absence – almost like a bereavement when he looked at me with his blue puppy dog eyes, as if to say, ‘please – PLEASE – don’t get any sicker. We’ll somehow get you lungs.’ I recall jokes about assassination attempts on triathletes.

Thankfully, my sister had come back from London so she could spend the remainder of my time with me. I had been so shocked when she left in the February, it was as though my body had been hollowed out until I was a shell of skin and bone. For two weeks following my transplant, she didn’t leave my side. The night of my transplant, she was inconsolable. To see her like that was incredibly distressing and there was – until I did vipassana – much guilt associated with her, my parents and my friends feeling so unanchored and so very much in despair at my condition. I still find it hard to wrench my head and heart back to that space of seeing my loved ones not just feeling, but looking so adrift and hopeless. Literally hope-less.

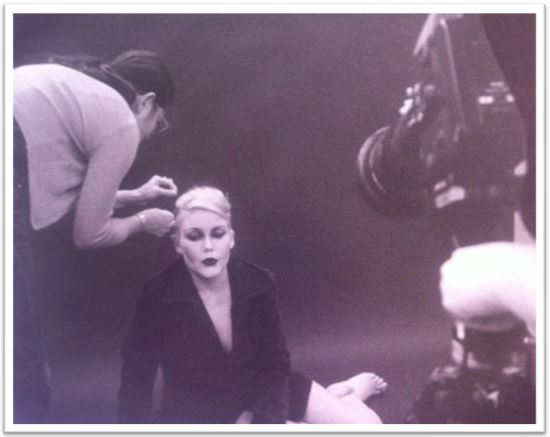

I have a series of images that were taken by my friend Alicia Alit-Trevatt, a fine photographer who I met in the January of 1998. Me and my transplant journey were to be her subject for her final piece of assessment for her photography degree. We signed all manner of legal waivers with the Prince Charles Hospital, for if I was to have the transplant while I was still the subject of Alicia’s project, she could be allowed entry into the theatre to take photographs of my surgery. As luck would have it, Alicia was also an intensive care nurse which bought us of lot of clout. The doctors and surgeons were more than happy to have her in the O.R should the transplant proceed. This is one of Alicia’s first images of me (a photo of a photo, so not the best quality).

For nine months, Alicia followed me around to all manner of appointments, parties (there were a lot of parties in 1998, and so much drinking), outings and modelling shoots like the one below. By another strike of grace, I was disconnected from my port-a-cath for this nude shoot with my friend Sharon Danzig.

Yep – that jacket came off

In the days preceding my transplant, I was in chronic pain and on morphine (before palliation was an option for Cystic Fibrosis), as my lungs had shrunk and essentially died from a lifetime of infections, cysts and bleeds. I knew I was dying and wanted Alicia to be there as I went through the dying process.

But then the call came just after midnight on the 22nd August, and when I arrived at thePrince Charles after being transferred from the Mater, Alicia was there with camera in hand, her spirit shining. I think she knew it was going to happen. But we did, too. There was never a question as to whether the lungs were going to be ‘mine’ or not. My familyand friends had never heard about false alarms. I remember my Mum saying, ‘this is it. It’s going to happen. The lungs are yours‘ and I believed her.

I remember my transplant doctor Scott Bell saying ‘this isn’t going to be easy’, and Alicia must have depressed the button on her camera at around the exact time Scott told me this and about what lay ahead. I just wanted my old lungs out and the donor lungs in.

Here is a poem I wrote last year about my transplant experience.

“‘thrown’

When you’re thrown back into life, you’re thrown from a moving train.

That first thump and roll; the aches and bruises that follow

untether you from your carriage.

Going from an empty husk of a woman – all lily-white like a hollowed out cockleshell –

empty but for the roar when you nurse it against your ear -

that was me.

My tender armour covered a pod of barely working organs

where there was a flicker of movement in the rattle of wet lungs and a clogged throat.

*

I would see things from my bed because I couldn’t walk anymore.

My muscles had melted into small pockets of goo

and I’d bend my head to see the leaning moon,

so still on its haunches – lazy, laconic and deathly still.

I had always shunned the sun and watched the moon.

Silently I would call it; aching for it to speak with me or move just a little,

but there it sat like a mute friend – giving me the answers I needed -

a silent partner to ricochet off my rattling chest and bag of bones

where I’d reach into sapphire skies and pray for Bedouin.

I was all tied up on the wrong end of the dream, dripping time.

My chest cut open and sewn back together like a clam – a cautious cut.

Hurled back into life – that rattle now silenced and replaced

by the pulse of machines breathing for still bleeding lungs,

taken from another who was now dead,

and lowered into me like the hull of a virgin ship into water.

*

A rekindling; the universe wanted to keep me.

In the daytime, I would wake up

with eyes like a hunted here,

knowing I was alive because I could feel

that hose in my mouth and its slink down my throat.

But more, I felt the fire beginning to burn on my chest.

I’m at the coal face of my body,

wondering how I came to be here – alive and hurting -

all dry lipped surrender.

Mad as a circus cat,

it was an exercise in patience until the next time I woke up -

snapping and grabbing at the tube

until a milk filled syringe was emptied into my neck and I knew the fight was over.

When the tube was pulled, my cough was a projectile.

A quadrant of doctors, gathered in the corner like vultures,

laughing about some dialectical shit.

My first words – ‘get the fuck out of here!’

I was crying and trying to shout with my wretched vocal cords.

They moved to the desk and I shouted ‘you disrespectful cunts!’

I never saw those doctors again and that was probably best – for them.

This was the first time I’d been thrown.

Thrown onto an operating table, flung into recovery,

sucked back into the furnace of theatre and ferried out again.

Funnelled into a solitary pod, the hose wrenched from my raw throat

and then I – throwing doctors out on their asses.

”